During my girlhood, I can remember running barefoot through a creek that cut through our neighbor’s backyard with my brother. We were pretending to be wayfarers, and I had absolutely no concern with the leaves caught in my hair, the sticks that scratched my skin, or the intertwined branches that held hands swinging above the water and me. My brother and I were dedicated to adventure without reserve, and being beautiful was not on the to-do list.

One day, a lady named Mrs. H drove her car over the bridge we had been playing underneath. When she saw us, she pulled her car over to the side. As I looked up, she was reaching her chin over the edge of the bridge’s wooden railing, looking like a gargoyle. She looked down at us to see if we were safe first, and then, gave a disapproving grimace.

“Did someone flip you upside down and use you as a mop?” she echoed.

“It looks like you have a rat's nest on top of your head. Get out of that mud, go home to take a bath, and run a brush through that thing!” she chastised.

“If you don’t, I’ll call your mother.”

We paused obliviously, and we didn’t listen. So inevitably, Mom was called, but she wasn’t upset. We were just on one of our adventures. Yet, from that day forward, she let me borrow her large claw clips to wrap up my curls in a bun so they wouldn’t frizz up and collect souvenirs.

I vividly remember yearbook day in the 4th grade. Naturally, it started like any other. My mom dresses me in my cousin’s hand-me-downs and rushes us to eat our toast in the backseat of the car, the late bell about to ring any minute. Halfway through the day, my classmate, Jillian walks up to confront me about my picture day outfit

“There’s no way I’m going to allow you to take yearbook pictures looking like that!” Jillian says reproachfully.

I am puzzled, and she promptly rushes me into the girl's bathroom across from the playground like we were on some sort of rescue mission. She patted the red, iron sediment from the baseball field off my shoulder and the side of my hip. She folded the hem of my pants in half-inch increments, claiming that,“cropped pants will have to do. They’re better than sweats but not as good as shorts.” I stood looking at this 5th-grade girl with wide eyes, bewildered by her knowledge of style and femininity.

She took the hair tie from her bouncy ponytail, and she grabbed a fistful of fabric from the bottom of my checkered shirt, pulling me forward onto my toes before I could re-establish my balance. Crumpling it into a cotton ball, her hands proceeded to wrap it with the tie and tuck it under my belly button, explaining it was to “get rid of the terrible boxy shape.”

From that day forward, I didn’t let either of my parents pick my outfits for school.

When I first started middle school, I didn’t realize that I had acne. With innocence, I knew about the bumps on my nose because my classmates used to ask about them out on the playground or in reading class. But, this was not elementary school, and everything was about to change.

In steel drum band, two boys named Anthony and James were snickering across the classroom. They were pointing at me with their aluminum mallets. I couldn’t figure out what was so funny. So, I asked. Deliberately failing to stifle laughter, they said, “It looks like you have raspberries growing on your chest! There are so many giant pimples there. How do you put on your shirt in the morning?! You should pop them!” I asked to use the restroom, and I sought recourse in the seclusion of a bathroom stall.

From that moment on, the pain from popping pimples was oddly comforting, and I learned to rely on it as a sense of cathartic relief. Like the anticipation of tearing open the wrapping paper from a gift, the experience was destructive but satisfying.

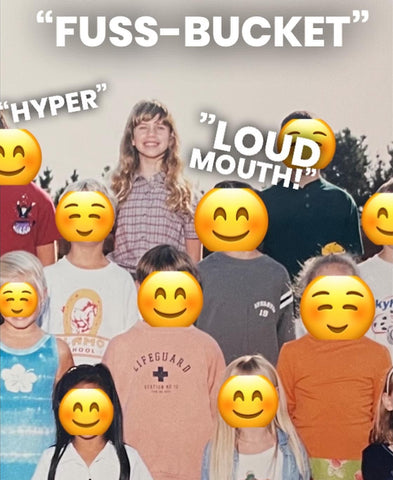

As I look back, the pressure young girls endure to achieve a specific image is unbelievable and unbearable.

And back in the 90s, we didn't even have social media to compare ourselves to!

So, makeup became a shield to cover my skin and an armor as I attempted to face the world. Makeup, my armor and shield, reflected the negative comments, the squints, and the glares. With layers of foundation, concealer, and powder, I was able to hide the acne, my true reflection. All the while, I was using makeup to close myself off from myself. Makeup was a wall that kept my real opinions, ideas, and personality in.

Little did I know that relinquishing these layers would be an emotional, 10-year process. Unless I was wearing a full face of makeup, there were times I couldn’t even show up to my family's breakfast table let alone leave the house.

I just felt like my physical appearance was a burden. By simply looking at me, I felt like I was decreasing their quality of life.

Isolation began to feel like a lonely, warm blanket. It disengaged me from the world in the midst of negative thoughts. Back then, the struggle to break pessimistic or self-destructive patterns was very grueling.

The best/worst decision I ever made was to expose my bare skin online. Thinking that nobody would see it. I could never have anticipated that it would urge me to face my insecurities head-on and work through them publicly with a community of people who felt the same shame upon looking in the mirror.

Today, I go out without makeup all the time. I no longer have panic attacks at red lights if I think that another driver is looking through their window at my skin. I have been able to take down the pieces of paper that I taped to my mirror, which for years at a time, prevented me from overanalyzing my skin and compulsively picking at my blemishes. Nevertheless, I still have moments where I feel unconfident without makeup. Before I go outside, I think to myself sometimes, “You should put on a little concealer.” If you want me to be honest, I still like the photoshopped version of myself better than the unedited one.

I am constantly striving to help myself and others like me to progress, not perfect themselves. Yet, it’s important to respect the fact that we still have those off days. In a world where we are continually bombarded with airbrushed images, celebrities who claim that they’ve never had plastic surgery procedures, and algorithms that prioritize superficial beauty, it can be a radical decision to simply proclaim that we love and accept ourselves the way we are. Simultaneously, this is a continual process that will be filled with many days that feel like regression rather than forward movement.

But isn’t that what progress is all about? Progress is the embodiment of embracing the days when everything isn’t perfect. It’s leaning into the discomfort of spontaneity. It’s also about accepting those moments and waves of dissatisfaction and choosing to navigate through them instead of trying to fight them and inevitably drowning.

If I could go back in time and tell younger me one thing, I would remind her that “what you look like has no impact on what you can do for this world. And in an image-oriented world that's run by expectations, finding ways to see your flaws as features is one of the most resilient and relentless things that you can do.”